Yak

Historically, the yak (Bos grunniens) has come to Mongolia through Tibetan monks and at the present, this long-haired, frost-hardy bovid lives predominantly in high mountainous areas of Mongolia: in the high Altai Mountain range, the Khangai Mountain range, and the Kharkhiraa and Khuvsgul mountains. In the Gobi Altai Mountains and Gurvansaikhan, there also are a limited number of yaks in the higher pastures. The average altitude is above 3200 meters above sea level. At this high elevation, the area has a harsh climate of cool moist summers, severely cold winters, and grazing restricted by short growing seasons.

Approximately 4.6% of the grazing land of Mongolia is located in the high mountain regions and is suitable for yak to graze.

Mongolian yaks are a kind of "hairy" cow — they know how to find forage grass underneath snow, which cows don't, and have other high altitude adaptations.

Though the livestock population of Mongolia was relatively constant for 60 years, their numbers increased rapidly over the last 10 years (by about a million/year, reaching 33.4 million in 1999) as Mongolia underwent a transition period from socialist system to the market economy and as livestock became privatized. The number of yak also increased in this period, by 42.5% between 1994 and 1999, so that there are now 813,300 yak registered in Mongolia.

During market economy period the number of yak heads are reduced due to natural disaster and its use for meat reproduction and in 2013 its number is 560,000.

Yak in Mongolia reside in very similar habitat to snow leopards. Yaks usually graze in high alpine pastures and are left to roam freely in the mountains in winter without protection. Yak graze on 49 species of vegetation. They generally move 3–5 km/day while grazing and rest under cliffs where it is easier for snow leopards to catch them.

Two types of yak can be distinguished in Mongolia, according to the area where they are raised - the Khangai and the Altai mountain yak.

Khangai yak

The large-framed Khangai yak stems from the traditional yak-keeping provinces of Arkhangai, Uvurkhangai, Bayankhongor and Khuvsgul. The type is large and fecund and is used for transport, meat and milk. Colors vary greatly and up to 90 percent of the animals are polled. They are good at compensatory growth and rapidly regain in the spring and summer the weight losses sustained over the previous winter.

Altai yak

As the name implies, these yak come from the Mongolian Altai region. The climate is characterized by great temperature fluctuations, inadequate precipitation and dry air. The average temperature over the year is 0oC and reaches a minimum of -30oC. The Altai yak is an alpine type and less good on the plateau. These yaks utilize the high mountain grazing, which do not provide a secure supply of feed and are frequently overgrazed. The yak is able to withstand long periods of nutritional deprivation. Colors are predominantly black or black and white. The majority has long, well-developed horns. The body is long and covered with thick hair. In reproductive terms, the Altai yak is similar to the Khangai. The Altai yak is thought to be capable of improvement, particularly in relation to meat production.

Yak has been mated with other cattle in Mongolia since earliest times. However, mating of pure yak cows to bulls of "improved" cattle breeds is not normally practiced in Mongolia.

For the first generation of hybrids, a distinction is made between yak cows mated to bulls of domestic cattle (Saran Khainag) and the reciprocal mating of females of domestic cattle with yak bulls (Naran Khainag).

There is celebrated the Yak Festival every year in Mongolia. The festival starts with the yak racing. The 20 minutes yak racing is probably one of the worlds slowest mounted racing. By the time the yaks arrive at the finish line, most of them are walking or barely trotting. Many untrained yaks give up the race half way.

The next competition is the yak lassoing. Some men on horses are scaring the yaks into running, while other men on the ground are lassoing the yaks. Once the contestant lassoes a yak, he has to fight to control the beast. Children contesting are simply dragged through the grassland.

The last yak-centered event of the day is the yak polo. It's great fun to watch the untrained and untamed beast running an undisciplined way around the field as the riders attempt to hit a ball with their hammer.

Yak down is a truly extraordinary luxury and exotic fiber. It is superior in many ways to other popular natural fibers:

- Yak down is 10-15% warmer than sheep wool.

- Yak down is similar in softness to cashmere, with a diameter ranging from 15-22 microns, but is far more durable.

- Yak down is hypo-allergenic and does not scratch against the skin as do many types of wool.

- Yak down remains very warm even when wet.

- Yak down is extremely breathable, contributing to self-regulation of body temperature.

- Yak down is very rare, adding value through interest and novelty when compared to popular and ever-present fibers such as wool or cotton.

Yaks produce two types of fiber: coarse outer hair and a fine down fiber that grows before the onset of winter as additional protection against cold. The down fiber is shed in early summer if not harvested and shedding is greatest from the belly of the yak and less from the back and rump. The down has, however, been used extensively by the textile industry as an alternative to other fine animal fibers since the 1970s. It is both combed and shorn to increase yield. Fabric made from yak down has a better luster than wool and provides a high degree of heat insulation.

-

04hours

Mongolian platinum yak down is one hundred times more rare than cashmere

Bodio’s has made a specialty and an art out of collecting, processing and knitting this ... -

04hours

Undyed yak down: Finally, a natural fiber that is as practical as it is exotic and luxurious

Cashmere is sublime and warm, but lacks lanolin to provide elasticity. Therefore even the most ... -

04hours

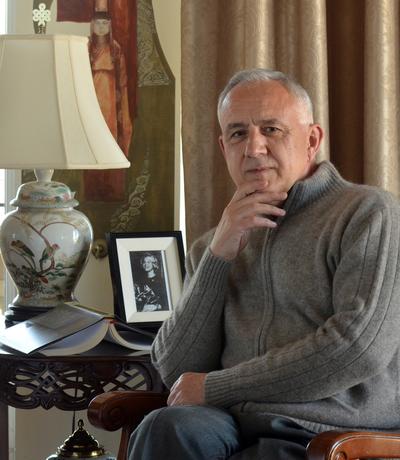

Fascination: sophisticated apparel from an untamed land of nomads and conquerors

Anthropology professor Jack Weatherford is the author of the New York Times bestseller Genghis Khan ... -

04hours

Do goats damage pasture? No they don't

Environmental issues are also of a concern for us. When it comes to cashmere business, ... -